Intro.

Regex (Regular Expressions) is like the magic wand of text manipulation to perform tasks like data validation, text manipulation, parsing, and more. It allows you to search for specific patterns of characters, such as email addresses, phone numbers, URLs, or any other custom pattern you define.

Metacharacters

In regular expressions (regex), metacharacters are special characters with a reserved meaning. They have a unique significance and are used to define patterns for pattern matching or text manipulation. When using regex, these metacharacters enable you to create more complex and flexible patterns to match specific strings or patterns within a text.

Here is a list of common metacharacters in regex:

Example:

Ruby script takes one command-line argument when executed. The input to the script is a string representing an IP address in the form of "127.0.0.x," where 'x' can be any single digit between 0 and 9.

#!/usr/bin/env ruby

puts ARGV[0].scan(/127.0.0.[0-9]/).join#!/usr/bin/env ruby: This is called a shebang line, and it indicates that the script should be run using the Ruby interpreter.puts: It is a Ruby method used to print the output to the console.ARGV[0]: This accesses the first command-line argument passed to the script..scan(/127.0.0.[0-9]/): Thescanmethod in Ruby is used to find all occurrences of a particular regular expression pattern in a given string. In this case, the pattern/127.0.0.[0-9]/is used. Let's break down the pattern:127.0.0.: This part of the pattern matches the literal characters "127.0.0." in the input string.[0-9]: This part of the pattern is a character class that matches any single digit between 0 and 9. So, the entire pattern matches an IP address in the format "127.0.0.x," where 'x' is any single digit between 0 and 9.

.join: Thejoinmethod is used to join all the matching occurrences found byscaninto a single string.

When you run the script with an IP address as a command-line argument, it will extract the matching part of the IP address (i.e., "127.0.0.x") and print it to the console.

Example usages and outputs:

Input:

./example.rb 127.0.0.2Output:127.0.0.2Input:

./example.rb 127.0.0.1Output:127.0.0.1Input:

./example.rb 127.0.0.aOutput: (No output, as it does not match the specified pattern)https://rubular.com/

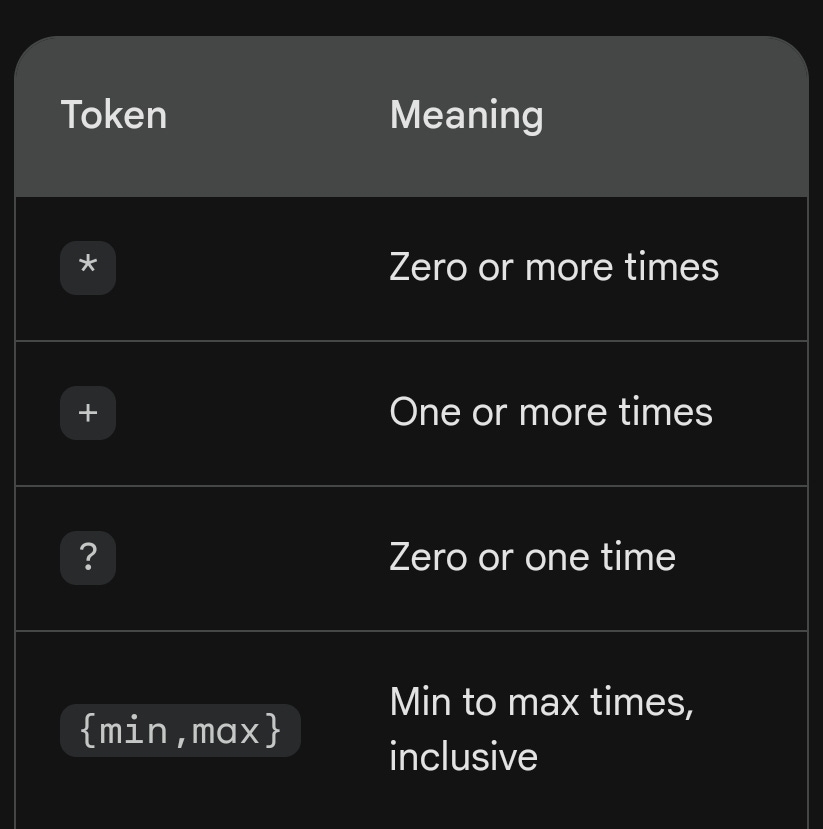

Repetition tokens

Used to specify how many times a particular token should be repeated in a regular expression. There are three main repetition tokens:

*- Matches the preceding token zero or more times.+- Matches the preceding token one or more times.?- Matches the preceding token zero or one time.

For example, the regular expression:

\d* matches any string of zero or more digits.

\w+ matches any string of one or more alphanumeric characters.

You can also use repetition tokens to specify a specific number of times that a token should be repeated. To do this, you use the syntax {min,max}, where min is the minimum number of times that the token should be repeated and max is the maximum number of times that the token should be repeated.

For example, the regular expression \d{1,3} matches any string of one, two, or three digits.

It's important to note that repetition tokens are greedy by default. This means that the regex engine will try to match as many repetitions of the token as possible. If you want to match a specific number of repetitions, you can use the

?quantifier after the number.For example, the regular expression

\d{1,3}?matches any string of one, two, or three digits, but it will only match exactly one or three digits if possible.

Here is a table summarizing the different repetition tokens in regex:

Table summarizing the different repetition tokens in regex.

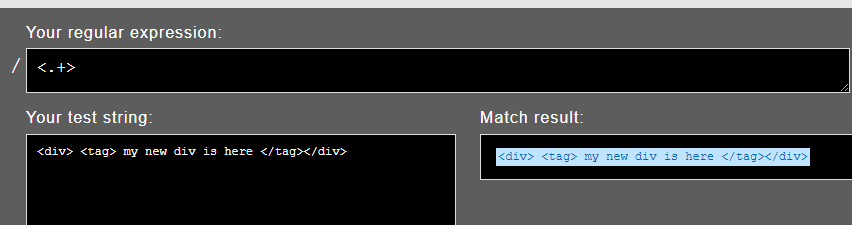

Greedy Matching:

Greedy behaviour causes the regular expression to match the entire string starting from the first "<" and ending with the last ">". It does not stop at the first ">" encountered.

Non-greedy or lazy matching

The regular expression <.+?> is a valid expression that uses non-greedy or lazy matching. It will match the shortest possible sequence of characters enclosed between `<` and `>`. Here's the breakdown:

- `<`: Matches the literal character "<".

- `.+?`: The dot `.` matches any character (except a newline) and the `+` means one or more occurrences. The `?` after `+` makes the matching non-greedy or lazy, meaning it will match the shortest possible sequence instead of the longest possible sequence. In this context, it will match any characters until it finds the first ">" encountered.

- `>`: Matches the literal character ">".

For example, given the input string: `<tag1> Some text <tag2> More text </tag2> </tag1>`, the regular expression `<.+?>` will match the following substrings:

1. `<tag1>`

2. `<tag2>`

3. `</tag2>`

4. `</tag1>`

Each match captures the shortest sequence of characters enclosed between `<` and `>`. Note that the non-greedy behavior is essential here to prevent the expression from matching the entire string as a single match (greedy behavior). If we were to use `.+` (greedy), it would match the entire string from the first `<` to the last `>`.

Backtracing

Backtracking is a technique used by regular expression engines to find matches for a regular expression pattern. It works by trying different possible matches, and backtracking if a match fails.

Backtracking is necessary because regular expression patterns can be ambiguous.

For example, the regular expression \w+ can match a string of one or more alphanumeric characters, or it can match a string of one or more spaces. If the regular expression engine encounters a string that could match either of these possibilities, it must backtrack to try the other possibility.

Backtracking can be a powerful tool for finding matches for regular expression patterns. However, it can also be inefficient, especially for patterns with a large number of possible matches.

There are a few things that can be done to prevent backtracking in regular expressions:

Greedy quantifiers, such as

*and+, will try to match as many repetitions of a token as possible. This can lead to backtracking if the pattern is ambiguous. Non-greedy quantifiers, such as*?and+?, will only match as many repetitions of a token as necessary. This can help to prevent backtracking.

Repetition tokens in regex

Repetition tokens in regex are used to specify how many times a particular token should be repeated in a regular expression. There are three main repetition tokens:

*- Matches the preceding token zero or more times.+- Matches the preceding token one or more times.?- Matches the preceding token zero or one time.

For example, the regular expression \d* matches any string of zero or more digits. The regular expression \w+ matches any string of one or more alphanumeric characters.

You can also use repetition tokens to specify a specific number of times that a token should be repeated. To do this, you use the syntax {min,max}, where min is the minimum number of times that the token should be repeated and max is the maximum number of times that the token should be repeated. For example, the regular expression \d{1,3} matches any string of one, two, or three digits.

It's important to note that repetition tokens are greedy by default. This means that the regex engine will try to match as many repetitions of the token as possible. If you want to match a specific number of repetitions, you can use the ? quantifier after the number. For example, the regular expression \d{1,3}? matches any string of one, two, or three digits, but it will only match exactly one or three digits if possible.

Possessive quantifiers in Regex

Possessive quantifiers in regex are used to ensure that the regex engine matches as many repetitions of a token as possible, without backtracking.

This is in contrast to greedy quantifiers, which will match as many repetitions of a token as possible, but may backtrack if necessary.

The syntax for possessive quantifiers is the same as for greedy quantifiers, but with a + sign added after the quantifier. For example, the regular expression \d++ will match as many digits as possible, without backtracking.

Here is an example of how possessive quantifiers can be used:

The regular expression \w++ will match any string of one or more alphanumeric characters, without backtracking. This means that the regex engine will not match a string of one or more alphanumeric characters, and then backtrack to match a shorter string.

Possessive quantifiers can be a useful tool for ensuring that your regex engine matches the correct string. However, it is important to use them carefully, as they can sometimes lead to unexpected results.

Backtracking is a recursive algorithm for finding all possible solutions to a problem. It works by starting with a partial solution, and then recursively exploring all possible extensions of that solution.

Here are two examples of possessive vs greedy quantifiers in regular expressions:

Possessive:

\d++

This regular expression will match as many digits as possible, without backtracking. For example, it will match the strings "12345", "123", and "1", but it will not match the string "12345a".

Greedy:

\d*

This regular expression will match as many digits as possible, backtracking if necessary. For example, it will match the strings "12345", "123", "1", and "12345a".

The main difference between possessive and greedy quantifiers is that possessive quantifiers will not backtrack, while greedy quantifiers will.

This means that possessive quantifiers are more likely to match the correct string, while greedy quantifiers are more likely to match a longer string than necessary.

Examples:

Groups:

In regular expressions, you can use parentheses () to create groups. These groups serve multiple purposes, such as defining a subexpression, specifying alternations, and applying quantifiers to a group of characters. To simplify groups, you can use non-capturing groups (?: ... ) when you don't need to capture the matched content.

For example:

Regular Expression:

(red|blue|green)Simplified Regular Expression:

(?:red|blue|green)

Backreferences:

Backreferences allow you to refer back to a previously matched group within the same regular expression. To simplify backreferences, you can use \1, \2, etc., to refer to capturing groups rather than repeating the entire pattern.

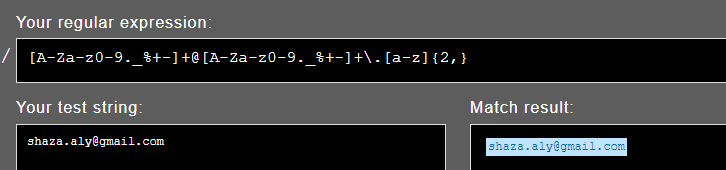

Practice : Email pattern:

Practice tips:

Word boundaries are useful when you want to match whole words rather than parts of words. They prevent partial matches and ensure that the pattern only matches when the target word is a standalone word and not part of a larger word.

For example, consider the word "cat" and the following text:

The cat sat on the mat. A category contains many items.If you want to match the word "cat" using the regular expression

\bcat\b, it will only match the first instance of "cat" in the sentence ("The cat sat on the mat.") and not the second instance ("category"), because the second instance is part of a larger word.^(caret) at the start of a regular expression: The caret^is called the "start of line" or "start of string" anchor.It asserts that the pattern that follows it should match at the beginning of a line or string. It does not consume any characters; instead, it only checks for a match at the specified position.

For example, the regex

^Hellowould match a line that starts with "Hello," but it won't match if "Hello" appears anywhere other than the beginning of the line.$ at end of line :

Called the "end of line" or "end of string" anchor. It asserts that the pattern that precedes it should match at the end of a line or string.

For example, the regex

^Hello$will only match the exact line or string that contains "Hello" and nothing else. It will not match "Hello, World!" or "Say Hello," but only a line or string that solely contains "Hello."

Resources: